Process Pending: the doing of art and science together in the 20th century

a chemist, a biologist, and a physicist walk into a bar... and walk out as humanities phd candidates

Before reading, please consider donating to the Al-Balawi family in Gaza.

I spent the last week in Oulu, Finland attending an environmental history conference, where Andrew, Hannah, and I presented some of the work we're doing as Glacial Hauntologies.

My orientation within Glacial Hauntologies has been to figure out how the doing of and thinking through the arts and humanities1 affects the doing and outcomes of science2. Physicist-philosopher Karen Barad engages in a similar practice she calls "diffraction", and refers to the reading through and practice of disciplines through each other as "intra-action"3.

There are a reasonable number of treatments (theses, books, articles, etc) that engage deeply with how scientific and engineering developments have impacted artistic movements4. There is significant literature on "art-science" and the doing of art and science alongside one another. There is a history (almost always deeply problematic, in many other ways) of producing art and science together pre-1900, e.g. Goethe, Humboldt, etc. But this last space, of how in the 20th and 21st century, the doing of science is directly impacted by, influenced by, intertwined with, diffracted through the arts, of how they can be done together in ways that do not just result in the making of art or the conceptualization of ideas, but that also do science—these are harder to find.

Below I present three interconnected examples that offer a lens through which this can be thought through and even, possibly, explicitly qualified/quantified/framed. One is Nakaya Ukichirō, a Japanese snow scientist who made the first artifcial snowflake. Another is the relationship between him and his daughter, the artist Nakaya Fujiko. And the third is a group Fujiko was a part of, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), which was founded by Bell Labs engineers and NYC artists in the 1960s.

Starting chronologically…

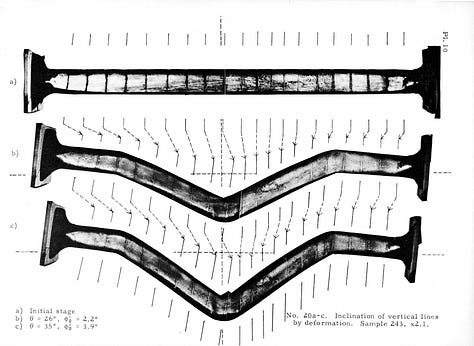

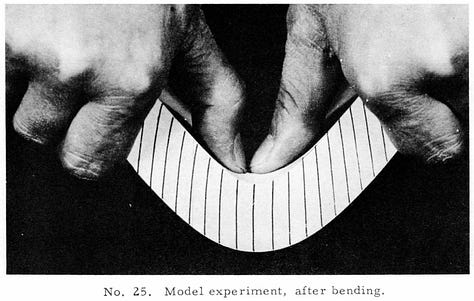

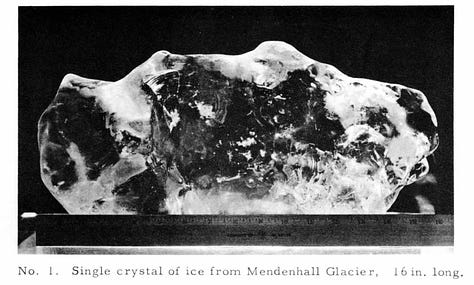

Nakaya Ukichirō was a Japanese snow scientist who gained international renown for being the first person to grow an artificial snowflake [cite]. I encountered him almost incidentally, through his work on the deformation of single ice crystals from the Mendenhall Glacier5 when compiling a review of ice fabric for my thesis. The figures in this report are extremely aesthetic, e.g.

The aesthetics of these images6 feel integral to the doing of the science. The technique, orientation, and contrast of the photographs, and the photographic technique used (Foucault's shadow photography), impact Ukichirō's ability to precisely observe and describe in detail what happens when you bend a single crystal of ice.

In addition to his work as a scientist, Ukichirō was a prolific essayist, poet, sumi-e artist, and, also, co-founded a film company responsible for thousands of popular scientific films. In primary school, he trained as a potter; his first scientific paper was (supposedly, I can't verify this myself) about Japanese porcelain. Only later, constrained by the lack of equipment and funding, did Ukichirō turn to snowflakes. Artistic training, inclination, and an observant, dedicated fascination with beauty, are woven throughout his work.

His daughter, Nakaya Fujiko, emerged in the the latter half of the 20th century as a sculpture and video artist. Her primary sculptural medium is fog—a precipitate of water, like her father's snowflakes7. E.A.T. invited her to collaborate on the Pepsi Pavilion at Expo '70 in Osaka, where she designed a fog sculpture that cascaded over the top of the pavilion.

For this, she collaborated with engineers and physicists in Japan and the U.S., in particular, Thomas Mee, an agricultural engineer. At the time, no atomizing/spray, water-based artificial fog machines could produce droplets small enough for Fujiko's work (e.g, small enough to drift and disperse). She tested other methods, like cooling systems to reach the local saturation point, but these were too energy intensive. But in the end, she worked with Mee, who developed a system of pin-jet nozzles that produced water droplets between 40-60 𝜇m.

While Fujiko declares that, "This was not a case of collaboration where art uses technology or vice versa. Rather it was a situation where technology gives courage to the artist to go on and be completely free", Mee has said that he had abandoned his development of a pure water fog machine, and it was this work with Fujiko, and her knowledge of cloud physics and fog generation, that reignited its development8. This system would eventually evolve into one used to cool cloud computing facilities9.

Finally, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) was founded by Bell Labs engineers (Billy Kluver and Fred Waldhauer) and artists (Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman) in the 1960s to facilitate one-on-one collaborations between artists, engineers, and scientists. Emerging from the performance 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering, they believed that "these collaborations could lead technology in directions more positive for the needs, desires, and pleasures of the individual, and benefit society as a whole." Over the next 20-30 years, these projects included, e.g., :

Island Eye Island Ear, an environmental concert that used "technology to reveal the visual, sound and physical properties of the island", and included scientific surveys of soil, vegetation, and water, parabolic antennas to create "discrete areas of sound", a kite performance, and Fujiko's fog sculptures.

the development of a (unrealized) projection system for an outdoor television system at the Centres Georges Pompidou

a Technical Services program that directly paired artists with engineers/scientists, and a lecture/demonstration program for new technologies like computer music, holography, and honeycomb structural papers.

Billy Kluver's work on satellite communications development for educational programs in India, e.g. "One research idea that E.A.T. pursued in Japan in the spring of 1970 that grew out of the experience of using Mylar and negative pressure to hold the mirror in place to create the large spherical mirror for the Pepsi Pavilion, and that was the idea of -- the idea of soft-dish communications antennas."

With Ukichirō, art (e.g., his training as an artist, his views on beauty, his eye for aesthetics, etc) shoots through his research like a mycelial network, nurturing and shaping the science. With Fujiko and E.A.T., I believe that a close look at the patents and academic papers produced by the associated scientists and engineers would show deep relationships to their artistic collaborations10. Art not just as inspiration or context, but as critical to the line of development and the process of experimentation.

This is work I would love to be funded to do (***manifesting***). I’m curious as to whether/how archives (e.g., patents, papers, notes, letters, documents, etc) show that collaboration with artists led to science/engineering developments/outputs. I aim to do this work without producing a narrative that implies art is only useful insomuch as it helps science. Instead, I believe the relationship is inherently entangled, and that these three examples, when examined closely, show in specific ways how art and science can be generative when done together. And I'm hopeful in particular, that my technical background in physics/engineering/glaciology, can offer a new perspective, one that takes a look at the evolution of the artistic and scientific in tandem.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please feel free to forward it to someone who you think might also like it. Click reply to let me know what you think of this essay and what you’re interested in hearing more about. I am trying out various formats to see what works. And if you’re not already, you can subscribe here:

momentarily treating arts (and humanities) as a monolith

momentarily treating all of science as a monolith

Barad, K. (2006) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822388128

just as two examples, Yuriko Furuhata's Climatic Media (2022) and Michelle Kuo's thesis (2018) on the group, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.)

Nakaya U (1958) "Mechanical Properties of Single Crystals of Ice. Part 1: Geometry of Deformation." U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Snow Ice and Permafrost Research Establishment (S.P.I.R.E.). This report caught my eye because it uses ice crystals from the Mendenhall Glacier, which drains out of the Juneau Icefield. I've taught on and help organize the Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP); for a moment, I thought—could Ukichirō have been involved in JIRP? But Ali Dibble looked through the JIRP records from that time; we haven't been able to find records of his involvement, just his use of these specimens

these images deserve a more formal treatment their aesthetic, but that day is not today

and Ukichirō also worked on fog dispersal in the 1940s

From the essay: Dyson F. (2006). And Then It Was Now. First published by Fondation Langlois FDL. Republished in the book accompanying the exhibition, Fujiko Nakaya. Nebel Leven. Haus der Kunst München. April 8 - July 31, 2022

As detailed in Furuhata, Y. (2022) Climatic Media: Transpacific Experiments in Atmospheric Control. Duke University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478022435

e.g., did Tom Mee file this patent based on the work he did with/for Fujiko? The timeline and description lines up.